Lesson Objectives

Trainees will be able to:

Identify some of the social and legal challenges newcomer migrants face when trying to find consistent and dignified employment in Washington D.C.

Recognize migrants’ struggles in finding stable housing, especially in relation to employment obstacles and the D.C. housing context.

Introduction

Migration to D.C. reflects the broader trends across the Americas, with a shift towards individuals fleeing not only economic hardship but also authoritarian regimes, violence, discrimination, and climate change impacts. This new context has deepened old challenges for migrants including language barriers, legal obstacles, access to education and health care, food insecurity, and discrimination. However, two overarching challenges–unstable employment and impossible housing– stand out as the most urgent.

Unstable Employment

Immigrants in D.C. have long faced work challenges which, today, are compounded by evolving migration patterns in the Americas that present new social and legal hurdles.

Social Barriers to Employment

Migrants have historically chosen destinations where they have relatives or established networks that can help them navigate employment obstacles and provide information on informal job prospects. However, in recent years, large numbers of migrants have been arriving (or have been sent) to a handful of interior cities—like D.C.—where they do not have relatives or networks, leaving them without the support of established immigrants.

Many migrants arriving in D.C. today, do not have this type of support. This is especially the case for the significant number of newly arrived Venezuelans, historically not a sizable population in the District. As a result, finding informal employment is not always a simple solution.

“Vinimos con una sobrina, vinimos los tres y no encontramos empleo, teníamos una aplicación, que era de mi sobrina, de hacer DoorDash y entonces en el auto andamos los tres recogiendo.”

“We came with a niece, so the three of us came here and we couldn't find a job, we did have the DoorDash application, which belonged to my niece so the three of us would go in the car doing pick-ups.”

Listen to Beatriz

Legal Barriers to Employment

While migrants often arrive in D.C. eager to start working–the majority face a number of challenges to accessing work, one being the limited avenues for legal employment.

While many migrants arriving in D.C. have experienced persecution or conflict, qualifying them as a “refugee,” others are fleeing economic hardship which does not substantiate an asylum claim. However, due to limited visa options for those fleeing economic hardship, asylum-seeking becomes the main avenue for many to obtain work permits.

Due to a lack of existing social networks, migrants (or asylum-seekers waiting to qualify for a work permit) face challenges to finding informal employment. When migrants do find informal employment, they risk facing wage theft, abuse, and work-place exploitation.

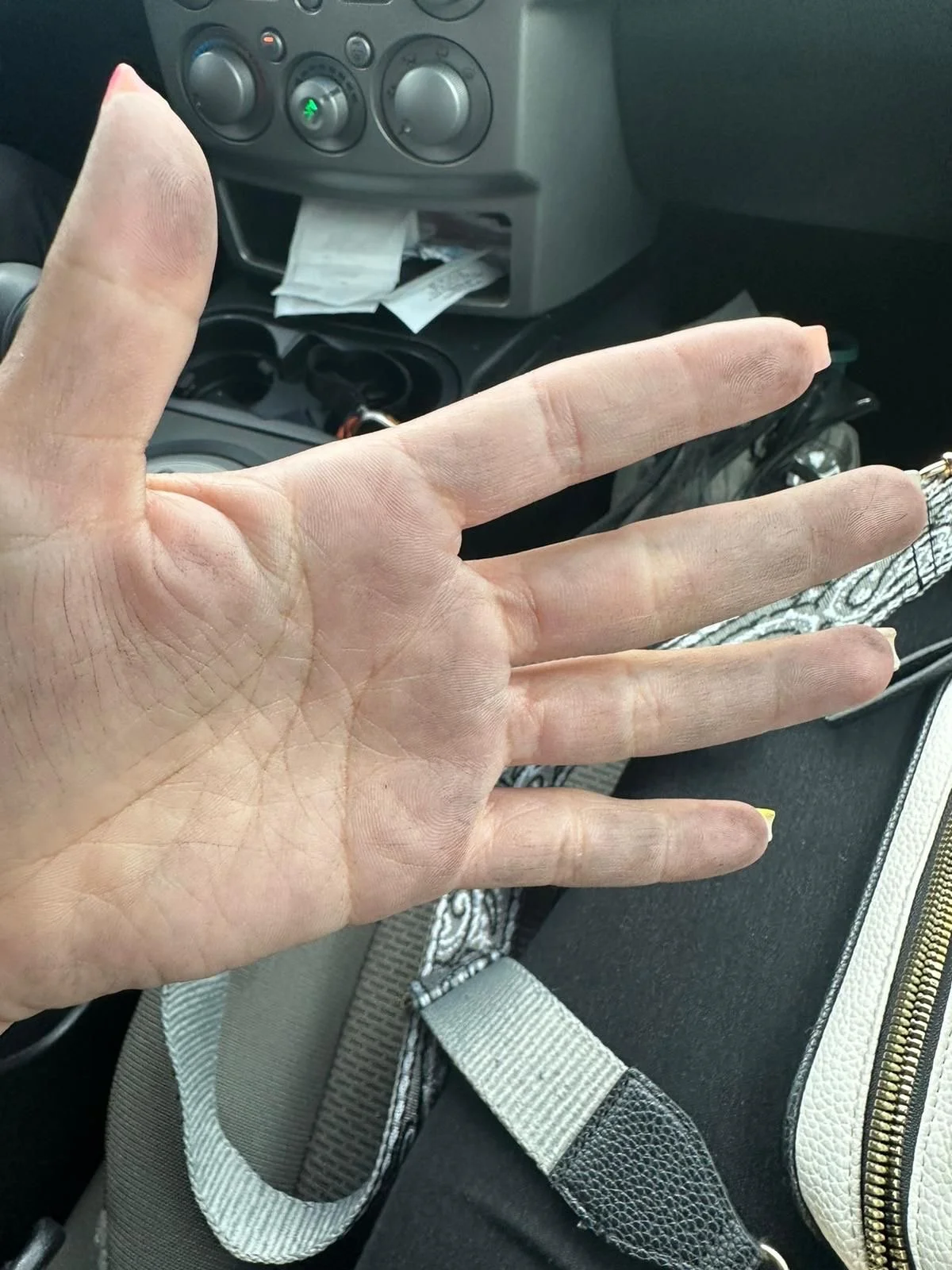

“Descansando después de 8 horas de trabajo para seguir en otra jornada de verdad q muy agradecida con este país de todo lo q me ha tocado vivir en este país 🇺🇸”

“Resting after 8 hours of work to be followed by another work shift, I am truly grateful to this country for everything that I have experienced here 🇺🇸”

“Aquí me ha tocado trabajar duro, pero nunca pensé trabajarlo en mi país y así como he trabajado duro he aprendido muchas cosas…por los menos yo llegué en diciembre del año pasado y empecé a trabajar en marzo, después que pasó el frío.”

“I have had to work hard, I have learned many things. It was difficult to get a job here. Here I have had to work hard, but I never thought I would work hard in my country and just as I have worked hard, I have learned many things…i arrived here in December of last year and I started working in March, after the cold passed ”

Listen to Marisol

To access formal employment, asylum-seekers need legal support to fill out asylum applications and—180 days later—request temporary work permits. This process is challenging, laborious, and costly. In addition to lawyer expenses, there is a fee of over $470 for work permit requests.

This applies to numerous migrants in D.C. pursuing Temporary Protected Status (TPS) applications. TPS offers work authorizations but not a path to permanent residency. As of 2024, the TPS application cost is $50, plus the work permit fee. Even if one is eligible for TPS and able to afford the application fees, applicants still confront a 10.2 month backlog for processing TPS applications and associated work permits.

As a result, finding stable employment becomes a daily concern for many migrants trying to re-establish themselves in D.C.

Legal Definitions of Migrants

The employment challenges migrants encounter often relate to how they are defined legally.

Refugee: Under the 1951 Refugee Convention and US law, a refugee is person who “owing to well-founded fear of being persecuted for reasons of race, religion, nationality, membership of a particular social group or political opinion” has been forced to leave their country and cannot return.

Asylum Seeker: Someone who has fled their country to seek refuge but is pending legal recognition as a refugee and awaiting a decision on their asylum application. Pursuing asylum is a fundamental human right, entitling individuals to seek asylum regardless of their circumstances.

Migrant: There is no universally accepted legal definition of a migrant, who is typically an individual residing outside their home country who is neither an asylum seeker nor a refugee. Although many may not meet the legal criteria for refugee status, they could still face dangers upon returning home. Regardless of their status, migrants are entitled to have all their human rights safeguarded in the country they relocate to.

Temporary Protected Status (TPS): TPS offers protection to individuals from select countries recognized by the United States as having undergone natural disasters or armed conflicts. Eligibility hinges on demonstrating presence in the US during the specified period and meeting additional criteria. TPS provides work permits but doesn't offer a direct pathway to permanent residency in the US. TPS status has been granted to a limited number of Venezuelans, Salvadorans, Hondurans Haitians and Nicaraguans.

While it is important to understand these legal differences, each human being is more than a legal identity and may even align with multiple legal identities throughout their migration journey

“Bien, por lo menos hemos conseguido trabajo allí, no todos los días se trabaja pero por lo menos si ya se toman en cuenta uno y estamos trabajando pero no todo los días pero trabaja. ”

“Well, at least we have found work, we don’t work everyday but at least one is taken into account and we are working, just not everyday. ”

Listen to Eriko

“...El tema del empleo, desde la fecha que nosotros por lo menos estamos acá, yo por lo menos no tengo empleo. No estoy trabajando. Estamos sobreviviendo porque él está trabajando, así que, todo está complicado, pero eso es parte de la migración, eso es parte de migrar, quizá no conocen que uno se enfrenta.”

“...The issue of employment, since the date that we have been here, I have not had a job. I am not working. We are getting by because he is working, so, everything is complicated, but that is part of migration, that is part of migrating, perhaps one does not know what they are face.”

Listen to Beatriz

When they do manage to find employment, migrants often find themselves working jobs they may have never imagined working in when living in their home countries. Even if migrants arrive in D.C. with high levels of education and professional certificates from home, these qualifications are not always recognized.

“Desde pequeño soñé que quiera ser policía en mi país y nunca me imaginé q llegaría estar aquí en los Estados Unidos”

“Since I was little, I dreamed and wanted to be a police officer in my country and I never imagined that I would end up being here in the United States.”

“Aquí bueno también aprendí un poco de arreglar caucho, de verdad estoy agradecida con este país de lo q me ha brindado jamás pensé trabajar todo lo q eh trabajado y aprendido aquí”

“Here, well, I also learned a little about fixing rubber, Aquí bueno también aprendí un poco de arreglar caucho. I am truly grateful to this country for what it has given me. I never thought I would work on everything i have worked and learned here.”

“Eso también allí mismo…allí en limpieza…Allí también sacan toda la basura de toda la sección, toda la basura, las bolsas la limpieza, mientras que uno va limpiando todas las…, vamos reuniendo toda la basura en esos carritos para llevar por que son seis pisos.”

“This one as well is there, if cleaning. There they take out all of the garbage from the entire section, all of the garbage, the cleaning bags, while you go around cleaning, gathering all the garbage in those carts to take away because there are six floors.”

Listen to Eriko

Impossible Housing

The challenges to stable employment create a context in which finding housing is close to impossible for most newcomer immigrants, an issue that is compounded by a general housing crisis in D.C.

Homelessness in D.C.

In 2014, D.C. faced a homelessness crisis prompting Muriel Bowser to run as mayor on a campaign to end homelessness. Once in office, Bowser’s initiatives led to a reduction in family homelessness.

However, by 2023, the homeless population increased by 18% due to the end of pandemic-related programs, rising costs, and budget constraints. Budget cuts, particularly in emergency rental assistance and housing vouchers, drew criticism for inadequately addressing homelessness, an issue directly related to racial justice considering the fact that 83% of individuals experiencing homelessness in the city are Black.

Tents in front of Union Station in DC. Flickr/psinderbrand

Arriving in a city already struggling to meet the housing needs of its residents, newcomer migrants have frequently been pitted against D.C. residents—specifically marginalized D.C. residents—by local government officials and the public. Meanwhile, D.C. residents and newcomer migrants alike are forced to sleep on the streets or in cars throughout the city.

“Era el punto de vivir, el auto era nuestra casa, nuestro todo, empezamos a sentir. Y esa noche, bueno, por último entregamos un pedido [de DoorDash] en Capitol y entregamos un pedido buscando un lado donde nos vayamos a dormir. Y ahí donde entregamos el último pedido lo hicimos, como en un lado, y parqueamos el carro y nos quedamos ahí, dormimos allí esa noche. Y no sólo fue esa noche pero un mes y cinco días durmiendo en el auto y en ese lugar porque pues no sabíamos pa’ dónde irnos ni nada.”

“It was the point of living, we began to feel like the car was our home, our everything. And that night, well, we finally delivered a [DoorDash] order to Capitol and we delivered the order while looking for somewhere to park and sleep. And there, where we delivered the last order, we parked the car and stayed there, we slept there that night. And it wasn't just that night but a month and five days, sleeping in the car and in that same place because we didn't know where to go or anything. ”

Listen to Beatriz

A Lack of Affordable Housing and Migrant Shelters

The DC area, like many U.S. cities, grapples with a severe shortage of affordable housing, particularly for low-income renters. To afford a two-bedroom rental in 2022, one needed to have an income of at least $73,520, a cost that is out of reach for many residents, even with rental subsidies and aid.

Newcomer migrants face additional barriers to finding stable housing including the inability to quickly obtain work permits, gather funds to pay for security deposits and rent, obtain DC-issued identification cards proving residency, and open bank accounts.

“Y un día una señora nos preguntó que hacíamos allí, como yo era algo peligroso – “no, nosotros no somos nada malo, venimos, estamos buscando empleo, da da da” — y verdad ya ellos no molestaron más, como que creyeron lo que le hemos dicho. Y ya todos los días nos quedamos allí hasta que ya cuando él ya cobró su primer sueldo allí buscamos una habitación y así estamos, vamos saliendo.”

“One day, a woman asked us what we were doing there, as if I was something dangerous. I said “no, we are not bad at all, we come looking for a job.” and truth be told, they didn’t bother us anymore, as if they believed what we were saying. So we stayed there everyday until he received his first paycheck and from there we looked for a room and that is how we are going now.”

Listen to Beatriz

Due to these barriers, when the District started receiving large numbers of migrants in 2022, D.C.’s Department of Human Services (DHS) established temporary lodging facilities under the Office of Migrant Services (OMS) to shelter newly-arrived migrants.

Within the first year of the opening of the first shelter at the Days Inn on New York Avenue, over 2,000 people, including over 516 children had stayed in these facilities. Compared to 1,250 OMS shelter residents in April of 2022, in March 2024, only 637 migrants were housed in two of the three temporary lodging facilities as DHS stopped accepting new migrants and planned to shut down the Days Inn facility.

“El arrendamiento en DC es costoso. Estoy en una situación en que yo necesito una casa grande porque tengo mucha familia, una casa de ese tamaño es necesario, algo de dos habitaciones. Necesito algo económico pero no me quiero ir de DC porque pierdo beneficios. Mis hijos están yendo a una escuela bien que les gusta, tenemos seguro médico. Pero tengo que buscar algo porque mi refugio acá [en el Days Inn] termina en enero.

“Renting in DC is expensive. I am in a situation where I need a big house because I have a large family, so a house of that size is necessary, something with two bedrooms. I need something affordable but I don't want to leave DC because I lose benefits. My children are going to a good school that they like, we have health insurance. But I have to look for something because my refuge here [at the Days Inn] ends in January.”

Deisy

While the hotels were intended to provide temporary emergency housing, families were never given a move-out date and ended up with months to year-long stays. While shelters serve as makeshift homes for migrant families across the country, most are keen to leave due to poor conditions and a desire for self-sufficiency.

“Para nosotros fue duro acá porque, o sea, no era lo que pensábamos, pensábamos que íbamos a conseguir empleo fácil y todo y no ha sido así, pero pues aquí estamos. El auto nos sirve muchísimo porque fue nuestra casa, nuestro todo, nuestro transporte y todo. Y no ha sido tan fácil acá en este pero yo sé que todo poco a poco irá mejorando hay que ser un poco paciente y, pues, seguir confiando en Dios.”

“For us it has been was hard here because, I mean, it wasn't what we thought, we thought we were going to easily get jobs and everything and it hasn't been like that, but here we are. The car helps us a lot because it was our home, our everything, our transportation and everything. It hasn't been so easy here during this time, but I know that everything will improve, little by little, we have to be a little patient and, well, continue trusting in God.”

Listen to Beatriz

Reflection Questions:

Using examples shared by our protagonists, how are the legal, employment, and housing challenges facing migrants interconnected?

Based on this lesson and your own experiences, in what ways are the challenges migrants face similar or different to those facing residents? Use the case of D.C. or your hometown for examples.